A moral panic is a feeling of fear spread among many people that some evil threatens the well-being of society.[1][2] It is “the process of arousing social concern over an issue – usually the work of moral entrepreneurs and the mass media“.[3]

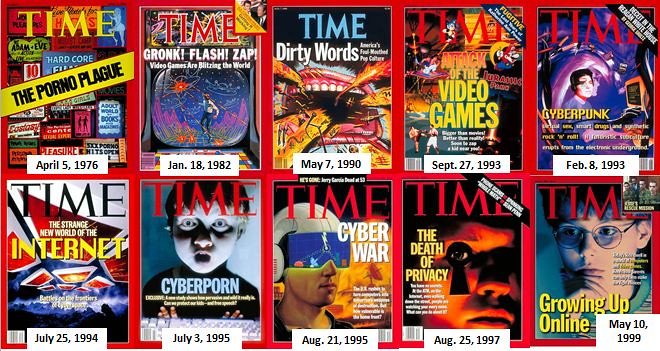

In recent centuries the mass media have become important players in the dissemination of moral indignation, even when they do not appear to be consciously engaged in sensationalism or in muckraking. Simply reporting the facts can be enough to generate concern, anxiety, or panic.[4][need quotation to verify] Stanley Cohen states that moral panic happens when “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests”. Examples of moral panic include the belief in widespread abduction of children by predatory paedophiles,[5][6][7] belief in ritual abuse of women and children by satanic cults,[8] concerns over the effects of music lyrics,[9] the belief that Juul ads target youth, youth attraction to flavors anymore than adults are,[10] [11]experts fearing kids growing dependence on nicotine from vaping and its epidemic rise[12] [13]are marketed moral panics including vaping related deaths which are not nicotine related as mass media suggests but from street versions of thc vape products. [14] These thc vape-related deaths would better fit with another moral panic- the war on drugs,[15] and other public-health issues.

Some moral panics can become embedded long-term in standard political discourse, e.g., note concerns about “Reds under the beds”[16] and about terrorism.[17]

Marshall McLuhan gave the term academic treatment in his book Understanding Media, written in 1964.[18] According to Stanley Cohen, author of a sociological study about youth culture and media called Folk Devils and Moral Panics (1972),[19] a moral panic occurs when “…[a] condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests”.[4] Those who start the panic when they fear a threat to prevailing social or cultural values are known by researchers as ‘moral entrepreneurs‘, while people who supposedly threaten the social order have been described as ‘folk devils‘.

British versus American

Many[citation needed] sociologists have pointed out the differences between definitions of a moral panic as described by American versus British sociologists. In addition to pointing out other sociologists who note the distinction, Kenneth Thompson has characterized the difference as American sociologists tending to emphasize psychological factors while the British portray “moral panics” as crises of capitalism.[20][21]

British criminologist Jock Young used the term in his participant observation study of drug taking in Porthmadog between 1967 and 1969.[22] In Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order (1978), Stuart Hall and his colleagues studied the public reaction to the phenomenon of mugging and the perception that it had recently been imported from American culture into the UK. Employing Cohen’s definition of ‘moral panic’, Hall et al. theorized that the “…rising crime rate equation…” performs an ideological function relating to social control. Crime statistics, in Hall’s view, are often manipulated for political and economic purposes; moral panics could thereby be ignited to create public support for the need to “…police the crisis”.[23]

Cohen’s stages of moral panic

According to Stanley Cohen,[4] who seems to have borrowed the term from Marshall McLuhan (see above), there are five key stages in the construction of a moral panic:

- Someone, something or a group are defined as a threat to social norms or community interests

- The threat is then depicted in a simple and recognizable symbol/form by the media

- The portrayal of this symbol rouses public concern

- There is a response from authorities and policy makers

- The moral panic over the issue results in social changes within the community

In 1971 Stanley Cohen investigated a series of “moral panics”. Cohen used the term “moral panic” to characterize the reactions of the media, the public, and agents of social control to youth disturbances.[4] This work, involving the Mods and Rockers, demonstrated how agents of social control amplified deviance. According to Cohen, these groups were labeled as being outside the central core values of consensual society and as posing a threat to both the values of society and society itself, hence the term “folk devils”.[24]

In a more recent edition of Folk Devils and Moral Panics, Cohen outlines some of the criticisms that have arisen in response to moral panic theory. One of these is of the term “panic” itself, as it has connotations of irrationality and a lack of control. Cohen maintains that “panic” is a suitable term when used as an extended metaphor.[4]

Mass media

According to Stanley Cohen in Folk Devils and Moral Panics, the concept of “moral panic” was linked to certain assumptions about the mass media.[4] Stanley Cohen showed that the mass media are the primary source of the public’s knowledge about deviance and social problems. He further argued that moral panic gives rise to the folk devil by labeling actions and people.[4]

According to Cohen, the media appear in any or all three roles in moral panic dramas:[4]

- Setting the agenda – selecting deviant or socially problematic events deemed as newsworthy, then using finer filters to select which events are candidates for moral panic.

- Transmitting the images – transmitting the claims by using the rhetoric of moral panics.

- Breaking the silence and making the claim.

Characteristics

Moral panics have several distinct features. According to Goode and Ben-Yehuda, moral panic consists of the following characteristics:[8]

- Concern – There must be the belief that the behaviour of the group or activity deemed deviant is likely to have a negative effect on society.

- Hostility – Hostility toward the group in question increases, and they become “folk devils”. A clear division forms between “them” and “us”.

- Consensus – Though concern does not have to be nationwide, there must be widespread acceptance that the group in question poses a very real threat to society. It is important at this stage that the “moral entrepreneurs” are vocal and the “folk devils” appear weak and disorganized.

- Disproportionality – The action taken is disproportionate to the actual threat posed by the accused group.

- Volatility – Moral panics are highly volatile and tend to disappear as quickly as they appeared because public interest wanes or news reports change to another narrative.[2]

Writing about the Blue Whale Challenge and the Momo Challenge as examples of moral panics, Benjamin Radford lists some of the themes he commonly sees in the modern versions of these phenomena:

- Hidden dangers of modern technology.

- Evil stranger manipulating the innocent.

- A “hidden world” of anonymous evil people.[25]