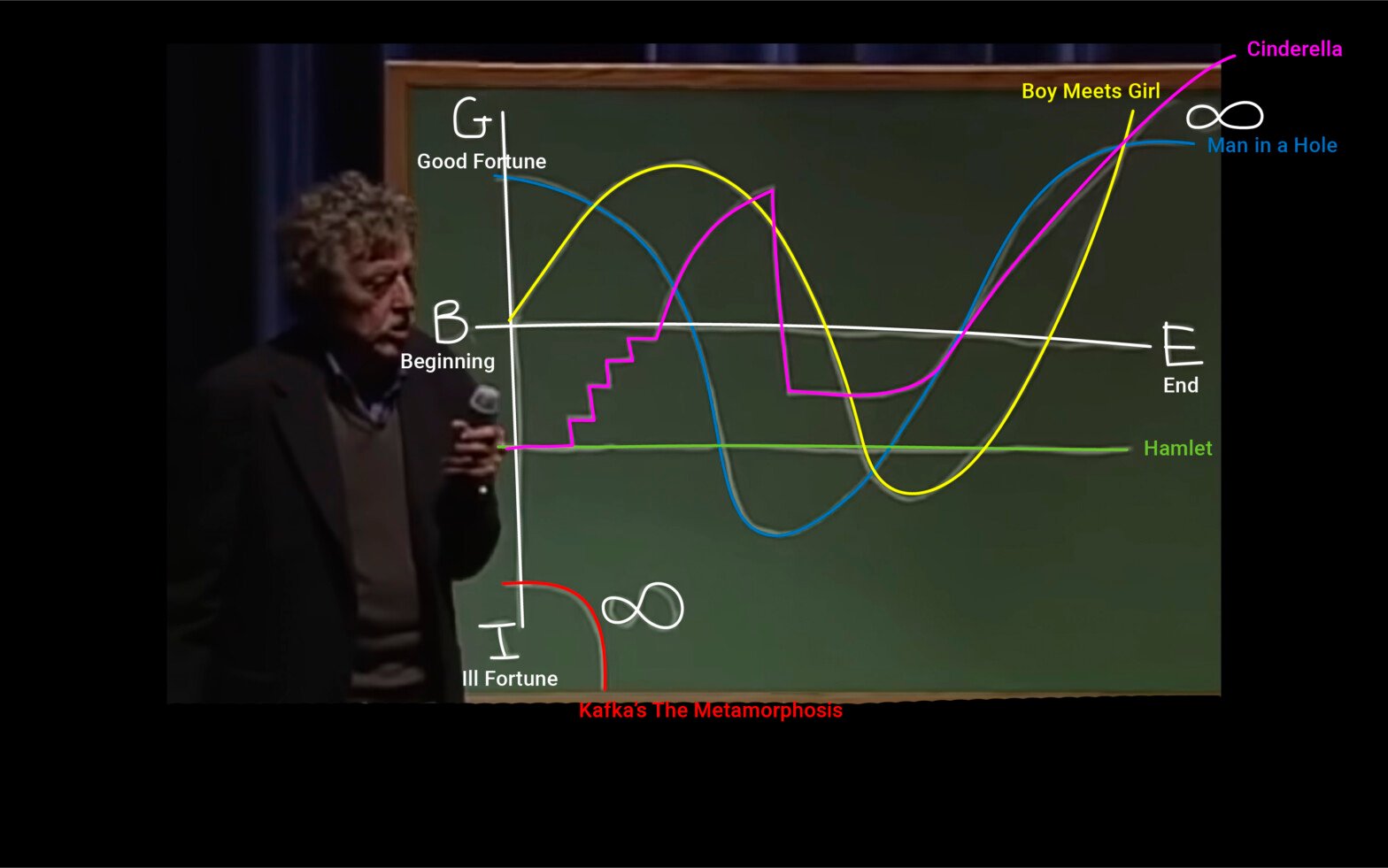

Kurt Vonnegut, Shape of Stories

Vladimir Propp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Propp

Vladimir Propp was born on 29 April 1895 in Saint Petersburg to an assimilated Russian family of German descent. His Morphology of the Folktale was published in Russian in 1928. Although it represented a breakthrough in both folkloristics and morphology and influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, it was generally unnoticed in the West until it was translated in 1958. His morphology is used in media education and has been applied to other types of narrative, be it in literature, theatre, film, television series, games, etc., although Propp applied it specifically to the wonder or fairy tale.

According to Propp, based on his analysis of 100 folktales from the corpus of Alexander Fyodorovich Afanasyev, there were 31 basic structural elements (or ‘functions’) that typically occurred within Russian fairy tales. He identified these 31 functions as typical of all fairy tales, or wonder tales [skazka] in Russian folklore. These functions occurred in a specific, ascending order (1-31, although not inclusive of all functions within any tale) within each story. This type of structural analysis of folklore is referred to as “syntagmatic“. This focus on the events of a story and the order in which they occur is in contrast to another form of analysis, the “paradigmatic” which is more typical of Lévi-Strauss’s structural study of myth. Lévi-Strauss sought to uncover a narrative’s underlying pattern, regardless of the linear, superficial syntagm, and his structure is usually rendered as a binary oppositional structure. For paradigmatic analysis, the syntagm, or the linear structural arrangement of narratives is irrelevant to their underlying meaning.

Criticism

Propp’s approach has been criticized for its excessive formalism (a major critique of the Soviets). One of the most prominent critics of Propp was structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who, in dialog with Propp, argued for the superiority of the paradigmatic over syntagmatic approach[6]. Propp responded to this criticism in a sharply-worded rebuttal: he wrote that Lévi-Strauss showed no interest in empirical investigation.[7]

Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index (ATU Index)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aarne%E2%80%93Thompson%E2%80%93Uther_Index

The Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index (ATU Index) is catalogue of folktale types used in folklore studies. The ATU Index is the product of a series of revisions and expansions by an international group of scholars: Originally composed in German by Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne (1910); the index was translated into English, revised, and expanded by American folklorist Stith Thompson (1928, 1961); and later further revised and expanded by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther (2004). Along with Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932), with which it is used in tandem, the ATU Index is an essential tool for folklorists.[1]

In The Folktale, Thompson defines a tale type as follows:

- A type is a traditional tale that has an independent existence. It may be told as a complete narrative and does not depend for its meaning on any other tale. It may indeed happen to be told with another tale, but the fact that it may be told alone attests its independence. It may consist of only one motif or of many.[2]

Critical response

In his essay “The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique”, Alan Dundes explains that the Aarne–Thompson indexes are some of the “most valuable tools in the professional folklorist’s arsenal of aids for analysis”.[9]

The tale type index was criticized by Vladimir Propp of the Formalist school of the 1920s for ignoring the functions of the motifs by which they are classified. Furthermore, Propp contended that using a “macro-level” analysis means that the stories that share motifs might not be classified together, while stories with wide divergences may be grouped under one tale type because the index must select some features as salient.[10] He also observed that while the distinction between animal tales and tales of the fantastic was basically correct—no one would classify “Tsarevitch Ivan, the Fire Bird and the Gray Wolf” as an animal tale because of the wolf—it did raise questions because animal tales often contained fantastic elements, and tales of the fantastic often contained animals; indeed a tale could shift categories if a peasant deceived a bear rather than a devil.[11]

In describing the motivation for his work,[12] Uther presents several criticisms of the original index. He points out that Thompson’s focus on oral tradition sometimes neglects older versions of stories, even when written records exist, that the distribution of stories is uneven (with Eastern and Southern European as well as many other regions’ folktale types being under-represented), and that some included folktale types have dubious importance. Similarly, Thompson had noted that the tale type index might well be called The Types of the Folk-Tales of Europe, West Asia, and the Lands Settled by these Peoples.[12] However, Alan Dundes notes that in spite of the flaws of tale type indexes (e. g., typos, redundancies, censorship, etc.; p. 198),[9] “they represent the keystones for the comparative method in folkloristics, a method which despite postmodern naysayers … continues to be the hallmark of international folkloristics” (p. 200).[9]

Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts – a catalogue

http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/folktexts.html – motiffs

http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/folklinks.html – general resources on stories

The ATU System

http://oaks.nvg.org/uther.html – Types of International Folktales and ATU Numbers

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/aarne-thompson-uther-tale-type-index-fables-fairy-tales

Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges, Christine Shojaei Kawan

Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges

Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges